Lacey Bubnash

AIA

Senior Associate

One of our recently completed projects in the Pacific Northwest is a building with a fascinating and unusual history. When the Maryhill Museum of Art in Goldendale, Washington, opened to the public in 1940, TIME magazine dubbed it “the world’s most isolated art museum.” Surrounded by ranch lands and wild terrain along the Columbia River gorge, Maryhill is a two-hour drive from Portland. The location is hardly the most eccentric thing about it, however.

For one thing, the building was originally intended as a home. Its owner, Sam Hill, was a Quaker businessman who moved from Minneapolis to Seattle in 1899 and became a big promoter of road-building in the northwest. A world traveler, he loved cars and convinced the state to build the Columbia River Highway, a 75-mile-long scenic route along the gorge.

Sam Hill, second from left, on the newly completed Columbia River Highway

Hill purchased a 5,300-acre site in Goldendale with the hope of founding a Quaker farming community. He asked the prominent architecture firm Hornblower and Marshall of Washington, DC, to build him a three-story mansion. Hill named the site Maryhill, after both his wife and daughter (although his family lasted only six months out west before heading back to Minneapolis without him). The idea was that it would be a chateau-like structure set on top of a hill, similar to the reinforced concrete home Hornblower and Marshall had already constructed for Hill in Seattle.

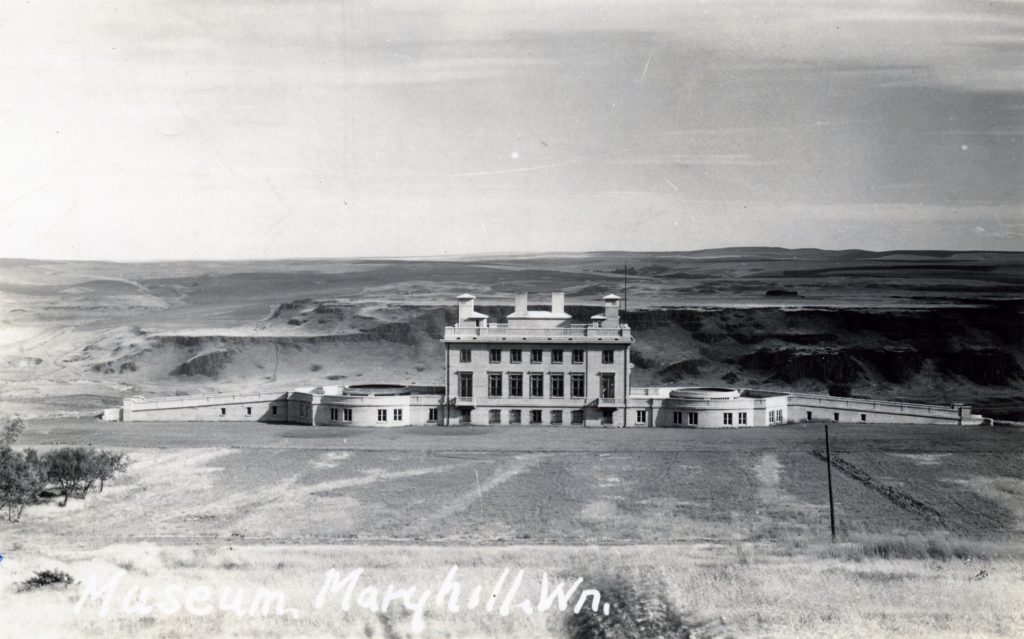

Historic view of Maryhill Museum of Art

Construction began in 1914. Experimenting with possible finishes, the designers included large pieces of stone in the concrete mix and intended to remove the forms before the concrete had fully set, ultimately washing or brushing out the cement to reveal the stone aggregate. Their concrete trial didn’t work, however, leaving the mansion with an unremarkable, board-formed concrete finish. It was decided to cover the concrete with stucco. Another of the building’s eccentricities: two massive ramps slope gently up to the east and west entrances, each one ending in a large circular terrace. Although now for pedestrian use only, the ramps were built so that visitors could drive up one ramp to the entrance, and then down the other ramp to a garage under the building.

Construction of the mansion halted in 1917 after the Maryhill Land Company failed. Hill’s globetrotting paid dividends, however. Loïe Fuller, a friend of his living in France, persuaded him to repurpose the building into a museum. A modern dance pioneer, she used her contacts to help Hill add to his collection, including more than 80 Rodin sculptures. Another friend of Hill’s, Queen Marie of Romania, brought 15 crates of artwork and artifacts to Maryhill in 1926 and dedicated the still-unfinished museum in a huge ceremony that attracted 2,000 people.

Queen Marie of Romania at the dedication of Maryhill Museum on November 3, 1926.

However, the museum’s completion proceeded slowly, and Hill died in 1931 before he could see his dream realized. It would take a third friend, Alma de Bretteville Spreckels, wife of sugar magnate Adolph Spreckels, to bring the museum to fruition. She donated art of her own and joined the board of trustees that had formed to run the museum. The Maryhill Museum of Art finally opened in 1940.

Before / after images of Maryhill Museum exterior restoration

The building’s stucco finish did not age well, with the first repair campaign undertaken in 1936, before the museum had even opened. In 2011, Architectural Resources Group was brought in to research past repair techniques and assess the current concrete and stucco conditions. The balustrade around the top of the building was in particularly bad shape due to water intrusion, and the ramps on both sides of the building had cracks along the walls near floor level. We recommended that the museum board not only repair the stucco, but also replace the roof and the waterproofing system on the ramps. Water infiltration was causing much of the damage and it was wise to address the underlying waterproofing issues before tackling the stucco repairs.

Before / after images of rooftop balustrade restoration

ARG ultimately ended up working closely with the general contractor and longtime museum patron, Schommer and Sons, to design stucco repair and waterproofing solutions appropriate for such an unusual building. Repairs were made to the balustrade, main building walls, and ramp walls, and new waterproofing was installed at the roof and both ramp decks. The close collaboration between the design and construction teams worked to ensure that the repairs and details will be durable, and to avoid altering any of the building’s historic details. The ramp paving was replaced with gray pavers that more closely resemble the historic driving surface than the previous, integrally-colored concrete paving.

It was a pleasure working on the building, not only because of its interesting history, but also because it presented an opportunity to view the fascinating artworks inside. The collection is eclectic, to say the least, with Victorian-era paintings, personal artifacts of Sam Hill, the gown Queen Marie wore to the coronation of her cousins Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra of Russia, Native American baskets, chess sets from around the world, art nouveau glass, and Orthodox icons. The entire second floor is dedicated to mannequins that were part of a 1945 exhibit at the Louvre. One-third the size of humans, these mannequins wear fashions created by France’s top designers after World War II.

Image by Josh Partee, addition in foreground by GBD Architects

If you end up visiting the museum, make sure stop by the life-sized replica of Stonehenge four miles east of Maryhill. Hill had it constructed to memorialize area men who died in World War I. Hill’s remains are buried on a ledge below the monument. Nearby, another large outdoor sculpture was installed on the site in 1998, designed by Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture. The large site installation, called The Overlook, brought Cloepfil national attention.

Maryhill was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. The nomination form has this to say about the museum: “Its appearance on the edge of the Columbia Gorge has been described as incongruous and unexpected as ‘a cowboy entering Windsor Castle with spurs jangling,’ but with a dignity that fits the grandeur of its surroundings.” Unsubstantiated rumors claim that the phrase “What in the Sam Hill?” was associated with the founder of Maryhill because of his unpredictable mind. He was a very eccentric man, but he left a significant legacy to the region. Now a key part of that legacy has been repaired, helping preserve the unusual stories behind this remote, one-of-a-kind museum on a hill.